As cited and cued in the article

Conjuring Eden:

Art and the Entheogenic Vision of Paradise

Entheos: Vol. 1 Issue 1, Summer 2001.

By Carl A.P. Ruck, Blaise D. Staples, Mark Hoffman

Images 31-40

Jump to images 1-10, 11-20,

21-30, 31-40, 41-50

[32] Vision of Ezekiel, with the Ascension

of Christ, miniature, Rabbula Gospels, Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana, Florence.

[34] Psalm 148, Narthex dome fresco,

Monastery Church of Koutloumousion, Mount Athos.

[35] Psalm 148, catalogue

of praisers, Narthex dome fresco, Monastery Church of Koutloumousion, Mount

Athos.

[31] Bosch, Temptation panel, Garden

of Delights Detail, Prado, Madrid.

[36] Alabaster bowl, Orphic cultic

initiation, late Roman, collection of J. Hirsch, New York.

[37] Phanes in "egg," Orphic relief,

Museum of Modena.

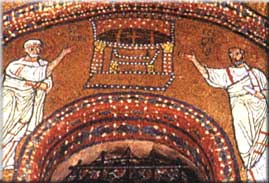

[38] Ascension mosaic, dome, Hagia

Sophia, Thessalonika.

[39] Empty throne, Italian manuscript

illumination.

[40] Franco Fabbro summary, mushrooms

and snails.

Sumnmary of Fabbro, Franco, "Mushrooms and Snails in Religious Rituals of Early

Christians at Aquileia," Eleusis, n.s. 3, p. 69 sq.

In his wonderful and surprising article, Frank Fabbro documents the depiction

of entheogenic mushrooms, namely Amanita muscaria, in the art of the Christian

Basilica of Aquileia in northern Italy. The section of the mosaic floor which

displays these mushrooms is found in the oratory of the northern hall, which

is the oldest part of the basilica, dating to before 330 AD. An epigraph in

the floor itself claims that the oratory was used for religious ceremonies.

That this mosaic depicts the entheogenic A. muscaria variety of mushroom is

strongly suggested by the fact that there are at least eight exemplars with

dark red caps, scattered with pale orange mosaic tesserae and with radiating

gill-shaped lamellae in the undersurface of the caps. Fabbro is correct in basing

his identification on the surprisingly detailed morphology as represented in

the ancient floor. The fact that medium to large sized red-topped, white shaped

mushrooms appear at all would be enough evidence to prove that early Christians

knew first hand of the entheogenic properties of A. muscaria.

However the careful addition of the scattered pale orange mosaic tesserae‚ can

only be understood in terms of the very distinctive white to golden spots‚ or

warts‚ of the A. muscaria, which distinguish it from other close varieties.

If these scabby remnants of the shattered white universal veil were intentionally

included in the mosaic, as they most certainly were, then the mushroom represented

could be none other than the A. muscaria.

It might be argued that these mushrooms are merely an ornamental element, similar

to that of the other plants and animals rendered in the floor, but this is surely

countered by the fact that the mushrooms are depicted in and around a bowl or

basket, unlike other ornamental motifs. It is difficult to image what artistic

purpose these bowls might serve other than to distinguish their contents as

edible. Fabbro recognizes this fact, and cites other scholars who have argued

that the two bowls suggest the ritual agape feast.

It is extremely fortunate for entheobotanists and students of early Christian

art that the mosaic floor in Aquiela has survived. All too often 'ornamental'

is a term used to describe plants, animals, and symbols whose iconographic significance

is not appreciated nor understood. This ignorance is a consequence of the often

esoteric nature of the icons under consideration.

Another bowl containing snails, probably of the variety Helix cincta. a favored

edible species, is found adjacent to the mushrooms. Fabbro hypothesizes that

the snails and mushrooms were eaten together. It is possible, however, that

snails were allowed to feed on the mushrooms, and then the snails were consumed.

This preparation may have effectively reduced or eliminated the undesirable

physiological effects of consuming the mushrooms directly. This is more likely

than it might sound initially; not only were the Romans well known for snail

breeding, but they recognized that what the snails fed upon had a determining

effect upon their flavor.

Fabbro also mentions that snails, as hibernating animals, are important symbolically

in that they represent death and resurrection. This mythological trait would

certainly not have been lost on the early Christians, whose initiation into

the cult was seen as a death and rebirth. Fabbro cites Brusin, G. & P.L. Zovatto,

Monumenti paleocristiani di Aquileia e di Grado, Doretti, Udine, 1957.

Click

below for the full online article